Karamat Ali, a legendary labour leader of Pakistan. Exactly one year ago, the people of Pakistan lost a leader whose absence is still deeply felt across the region. The death of Karamat Ali marked not only the end of an era for Pakistan’s labour movement but also a profound loss for South Asia, where his tireless activism and visionary leadership inspired generations of workers, activists, and ordinary citizens to fight for their rights. Karamat Ali was more than a trade unionist—he was the living embodiment of the “unrest soul,” a restless force for justice who never remained silent in the face of oppression, exploitation, or injustice.

Born in Multan two years before Partition, Karamat Ali hailed from a working-class family. His father worked in a textile factory, and his mother and sisters were home-based workers. This background shaped his lifelong commitment to the struggles of the poor and marginalised. He moved to Karachi in the 1960s, where his journey as a student and later labour rights activist began in earnest. From his early days as a student activist at Government Emerson College, where he led protests against the military dictatorship of Ayub Khan, to his later years as a mentor and institution builder, Karamat Ali’s life was defined by his unwavering dedication to social justice and human rights.

Karamat Ali’s activism was not confined to the factory floor or the union hall. He was a vocal advocate for a wide range of causes, always ready to stand up against injustice, whether it was the forced conversion of Hindus in Sindh, the plight of bonded labourers in the agricultural sector, or the government’s brutal crackdowns on the working class. His leadership was marked by a rare combination of courage, compassion, and strategic vision. He was not content to merely protest; he sought to build lasting institutions that could empower workers and marginalised communities for generations to come.

One of his most significant contributions was the founding of the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER) in 1982. Inspired by similar institutions abroad, PILER became a beacon of hope and learning for the working class, offering education, advocacy, and solidarity to workers across Pakistan. Under Karamat Ali’s leadership, PILER played a pivotal role in campaigns for workers’ rights, including the fight for compensation for the families of the 260 victims of the 2012 Baldia factory fire. He also championed the rights of home-based workers, peasants, and migrant labourers, and was a staunch opponent of child and bonded labour.

Karamat Ali: As a Social Reformist

Karamat Ali’s activism extended beyond labour rights. He was a leading figure in the movement for police reforms in Sindh, taking the government to court to demand accountability and transparency in law enforcement. His efforts helped to secure land rights for the residents of Khaskheli village in Sinjhoro, Sanghar district, and he was a vocal opponent of enforced disappearances, particularly in the cases of Hari and nationalist leader Punhal Sariyo. When the rights of peasants were threatened, as in the case of Ghulam Ali Leghari, Karamat Ali did not hesitate to take up their cause and fight for justice in the courts.

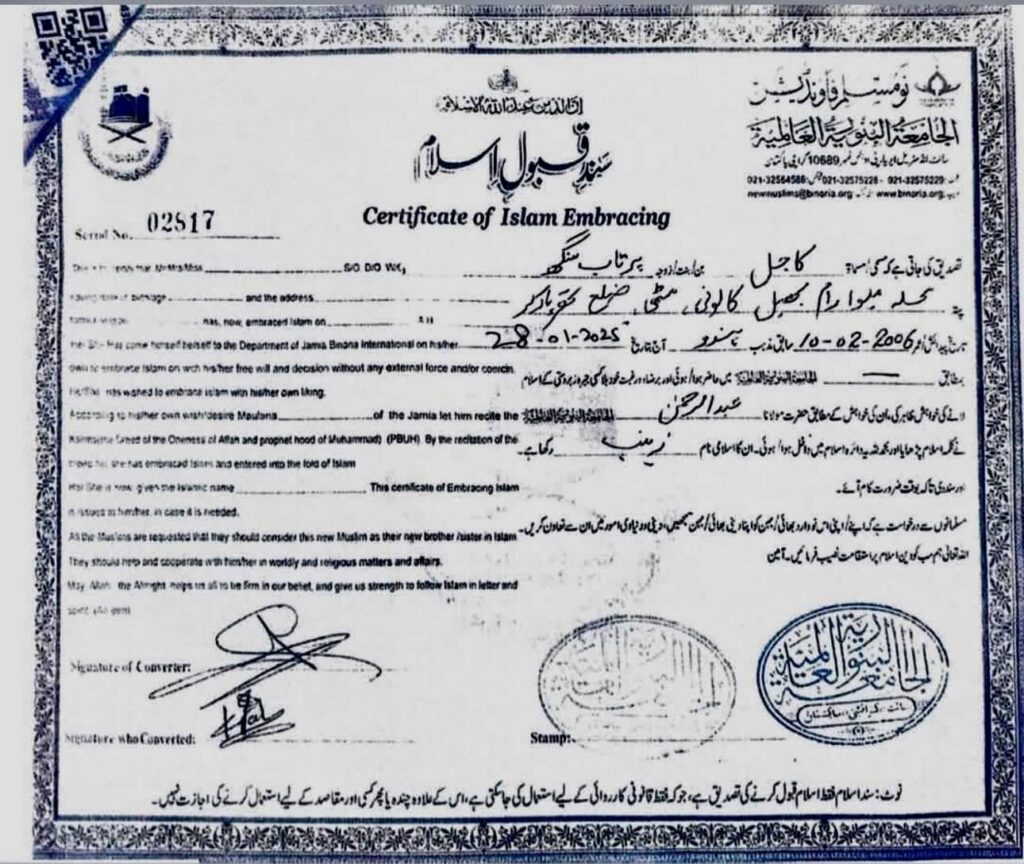

Perhaps one of the most striking aspects of Karamat Ali’s leadership was his commitment to those in need. When Hindu girls Rinkle Kumari and Ram Piyari Oad were kidnapped and forcibly converted, he not only led protests but also provided practical support to their families. At the request of lawyer Mustafa Lakho and a friend Raj, he allowed the parents and family of Ram Piyari to stay at PILER’s office for several weeks, offering them shelter and solidarity during their ordeal. This act of kindness and solidarity was emblematic of his approach to activism: he saw the struggle for justice as a collective endeavour, rooted in empathy and human dignity.

The passage of the 18th Amendment to Pakistan’s Constitution marked a watershed moment in the country’s educational landscape. For the first time, the right to education was enshrined as a fundamental right through Article 25-A, mandating that all children between the ages of 5 and 16 must receive free and compulsory education.

I can recall vividly the days when civil society organisations, led by the Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER), joined hands with like-minded groups to file a constitutional petition in the Sindh High Court. Their plea was simple yet profound: to compel the state to fulfil its constitutional obligation and ensure that no child in Sindh would be left behind. The court’s response was unequivocal—it directed the Sindh government to take immediate and effective steps to make education free and compulsory for all children in the province.

Spurred by this judicial intervention, Sindh became the first province in Pakistan to translate this constitutional vision into law. The Sindh Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2013, was passed with overwhelming support, setting a bold precedent for the rest of the country. The law not only guaranteed free schooling but also sought to break down barriers for disadvantaged children, ensuring that every boy and girl—regardless of caste, creed, or economic status—had the right to learn and grow.

Despite the legal framework and the government’s commitments, the full implementation of free and compulsory education remains a work in progress. Schools are still inaccessible for many, infrastructure is lacking, and millions of children continue to be denied their fundamental right to education.

Amid these persistent challenges, the vision of leaders like Karamat Ali shines brightly. As a tireless advocate for the marginalised, Karamat Ali championed the cause of education as a cornerstone of social justice and empowerment. PILER Centre is located in Gulshan-e-Maymar in Gadap Town of Karachi. Despite being part of Karachi Metropolitan Corporation, the area is always neglected by the urban rulers of the city. Karamat Ali started non-formal schools in various villages to provide formal education to those out-of-school children who cannot go to school due to the absence of school buildings or teachers.

How could I ever forget the resilience and compassion displayed by Karamat Ali during the devastating super floods of 2010? I was fortunate to be on the ground, actively participating in relief efforts that brought hope to thousands of lives shattered by the disaster. As flood waters swept through upper Sindh districts, a massive wave of internally displaced persons (IDPs) poured into Karachi, seeking refuge wherever they could. Many were provided temporary shelter in the under-construction apartments of the Labour Colony near Abdullah Gabol Goth—a place that soon became a symbol of collective humanity.

What stood out most was the immediate initiative taken to restore a sense of normalcy for the children. Amid the chaos, makeshift classrooms were set up in three shops and later at the community centre in the colony to ensure that education continued uninterrupted, while safe drinking water stations were established to protect families from disease.

But the response didn’t stop there. Recognising the urgent need for health and sanitation, PILER quickly mobilised the Pakistan Medical Association (PMA) and the Orangi Pilot Project, bringing essential medical care and hygiene facilities directly to the displaced.

Over 10,000 IDPs found sanctuary in Labour Square and at several unofficial camps—from Tharo Mangal Goth to the Northern Bypass and Super Highway near Maymar More. PILER’s relentless efforts ensured that each of these communities received food, shelter, and basic necessities. Yet, some of the most heart-wrenching stories emerged from the margins: a group of Scheduled Caste Hindus, barred from official camps due to religious discrimination, had to build their makeshift cottages near New Karachi. Even here, PILER’s team reached out, offering support and solidarity to those who had been forgotten by others.

Through it all, what shone brightest was the unwavering commitment to leave no one behind—a testament to the spirit of service and justice that defines PILER’s mission.

A voice of Voiceless

Karamat Ali was more than just a labour leader—he was the voice of those who had long been unheard, the champion of society’s most marginalized. His relentless advocacy for justice and equality earned him the trust and friendship of some of Sindh’s most prominent nationalist leaders, including Rasool Bux Palejo, Dr. Qadir Magsi, and Jalal Mehmood Shah. Karamat often invited these leaders to speak at PILER, creating a rare platform where diverse voices could unite for the common cause of social justice and democracy.

He spoke fondly of his close friendship with Rasool Bux Palejo, the legendary leftist and Sindhi nationalist leader. Karamat would recount stories of their shared struggles and the deep bond that united them, not just as comrades but as friends committed to the same ideals. One story in particular stands out for its courage and drama—a tale that Karamat himself would tell with visible pride.

At a high-profile event in Islamabad, General Zia-ul-Haq, then Pakistan’s military dictator, had just finished delivering a speech. As he was about to leave the venue, Karamat Ali stood up and deliberately stepped into his path. Security personnel tried to block him, but Zia, perhaps surprised by Karamat’s boldness, signaled for him to approach. Seizing the moment, Karamat asked the General why he was keeping Rasool Bux Palejo—an ailing leader of the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and a vocal opponent of military rule—behind bars. Zia exclaimed as he was unaware of Palejo’s situation but promised to look into it.

After the event, Karamat’s friends advised him to leave his lodgings immediately, fearing retaliation. But Karamat refused to run or hide. He stayed put, confident in the righteousness of his cause. True to Zia’s word, Palejo was eventually released—a victory that Karamat attributed to the power of standing up and speaking out. Later, Karamat personally arranged for Palejo’s medical treatment in London, ensuring that his friend received the care he needed.

This episode is just one example of how Karamat Ali’s fearlessness, integrity, and loyalty defined his leadership. He was not only a friend to the oppressed but also a bridge between communities and movements, always ready to challenge injustice—even in the face of overwhelming power.

Unyielding Legacy of a True Labour Leadership

Karamat Ali’s vision for Pakistan’s labour movement was both ambitious and pragmatic. He dreamed of a unified national-level trade union federation or confederation, recognising that only a strong, united movement could effectively challenge the forces of exploitation and oppression. To this end, he formed the National Labour Council, which sought to organise workers sector-wise rather than unit by unit. This innovative approach reflected his understanding of the changing nature of work and the need for new strategies to build workers’ power in the face of globalisation and neoliberal economic policies.

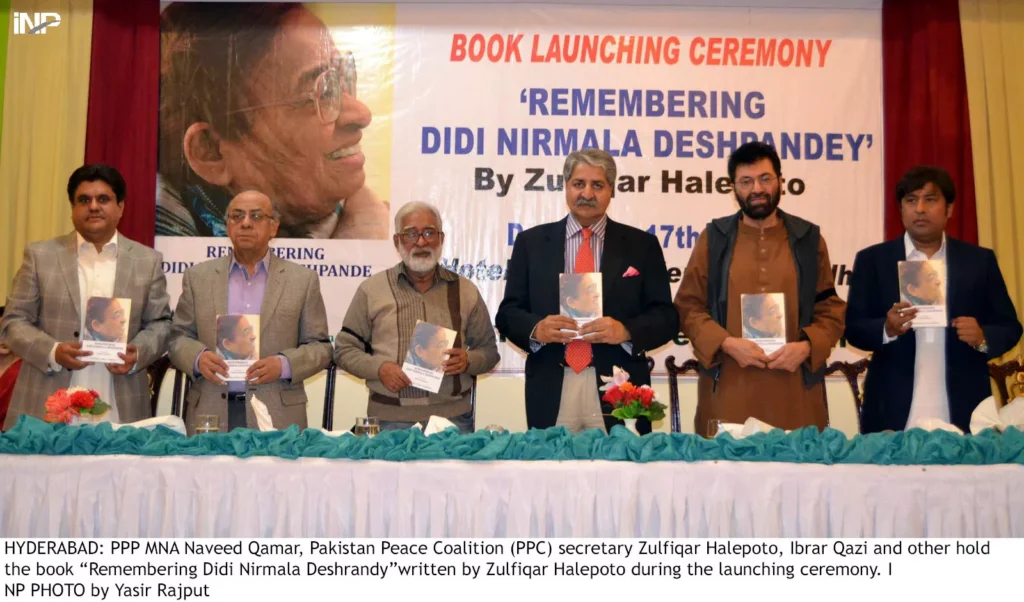

Karamat Ali’s legacy is not confined to Pakistan. He was a leading figure in the South Asian peace movement, co-founding the Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy, People’s SAARC and South Asia Labour Forum (SALF). He believed that peace and justice were inseparable, and he worked tirelessly to build bridges between civil society groups across borders. His efforts earned him international recognition, including the Didi Nirmala Deshpande Peace and Justice Award in 2013.

Even in his final years, Karamat Ali remained a tireless advocate for the rights of the oppressed. He was a mentor and teacher to many, and his loss is felt not only by his family and comrades but by all who believe in a more just and equitable world. As the Asia Europe People’s Forum noted, “With the passing away of Karamat Ali, we have lost one of the best trade union leaders of South Asia. AEPF mourns his loss, and at the same time, we celebrate his life and achievements.”

Karamat Ali’s life and work remind us that the struggle for justice is never easy, but it is always necessary. His “unrest soul” continues to inspire new generations of activists to fight for the rights of the marginalised, to challenge injustice wherever it appears, and to build a better future for all. In a world often dominated by cynicism and despair, Karamat Ali’s legacy is a beacon of hope and a call to action for all who believe in the possibility of change.