The debate over the creation of new provinces in Pakistan has periodically resurfaced, often presented as a populist measure to address administrative challenges or to fulfil longstanding regional demands. However, when the establishment floats such proposals, many in Sindh perceive them not as genuine solutions but as diversions designed to deflect attention from pressing socio-economic crises.

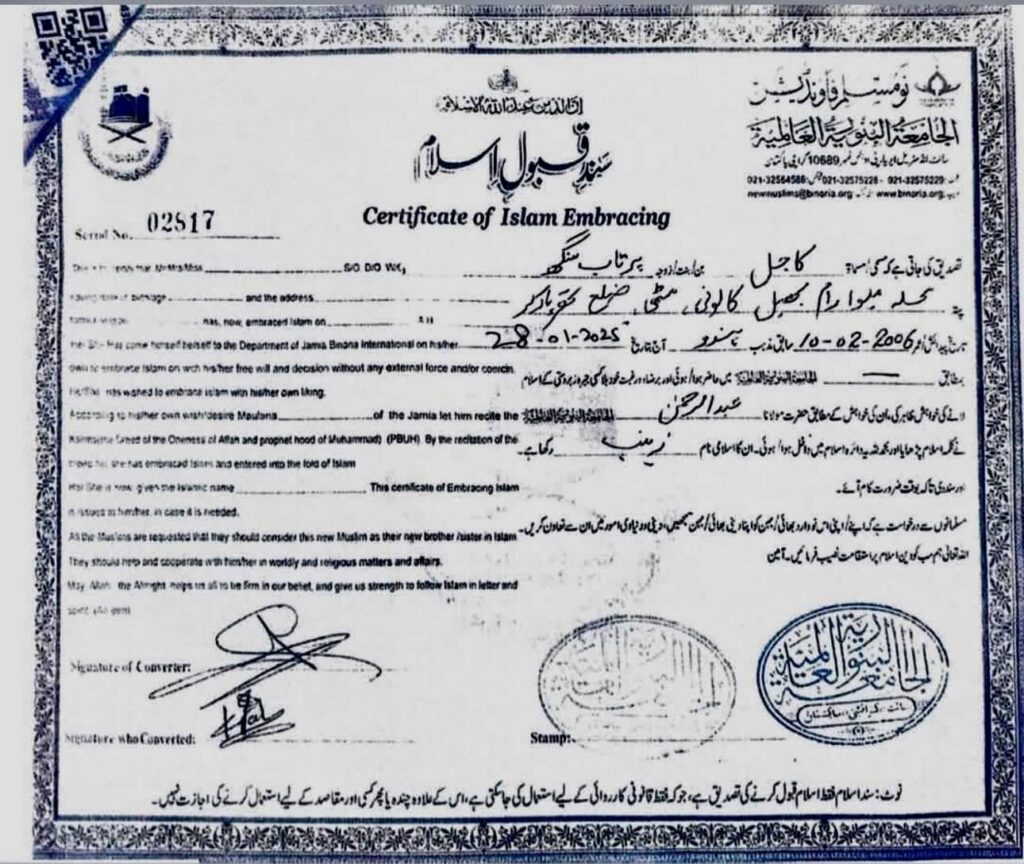

The Sindhi people, in particular, have consistently resisted attempts to divide their province, interpreting such moves as conspiratorial manoeuvres rooted in linguistic and ethnic politics, most notably driven by the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM).

For Sindhis, Sindh is not merely an administrative unit; it is an ancient homeland with a deep historical, cultural, and linguistic identity. The slogan “Marsoon, Marsoon, Sindh Na Desoon” (We may die, but will not let Sindh be divided) encapsulates the intensity of this attachment.

This resistance stems from the conviction that any attempt to carve out a “Mohajir province” or to redraw provincial boundaries along ethnic lines would undermine Sindh’s integrity, dilute its cultural identity, and weaken its political autonomy within the federation.

From a critical lens, the reemergence of this debate seems less about governance and more about politics of distraction. Pakistan currently faces multiple crises: inflation, unemployment, shrinking civic space, and a worsening law-and-order situation. Instead of addressing these structural problems, the establishment occasionally raises the issue of more provinces, knowing it will ignite polarising debates. This tactic shifts the public discourse away from accountability and reforms, trapping political actors into defensive postures.

The Sindhi nationalist and mainstream political circles interpret MQM’s push for a separate province as a continuation of its ethnic politics that emerged during the 1980s. The party, representing primarily the Urdu-speaking community of urban Sindh, has long demanded greater autonomy and resources, citing grievances of neglect and discrimination. Yet, Sindhi critics argue that MQM’s demands are not grounded in equitable development but in a communal vision that fragments society along linguistic lines. To them, creating a Mohajir province would institutionalise ethnic segregation and deepen fissures in an already fragile federation.

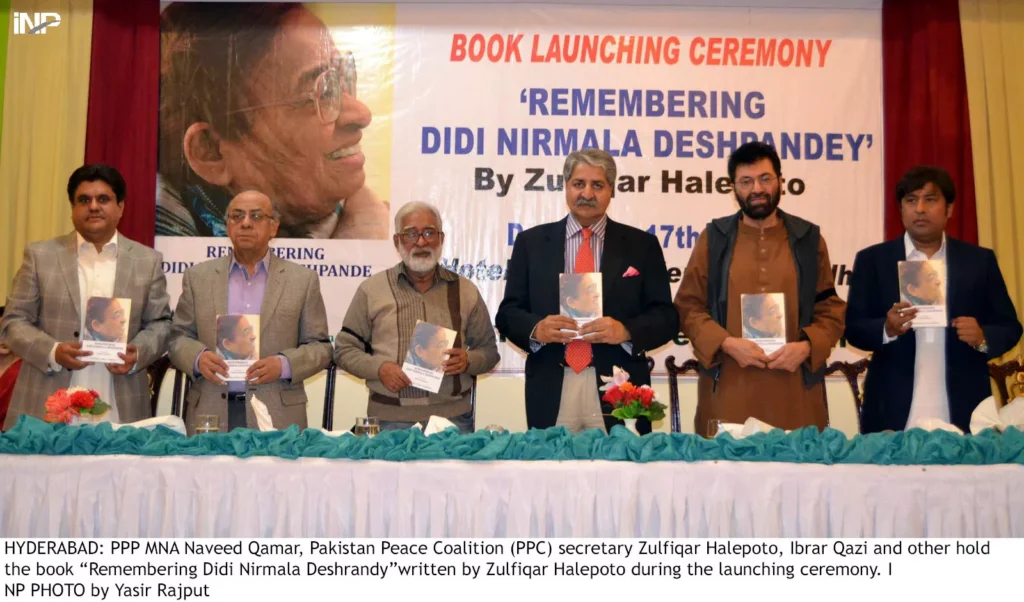

The Sindhi stance against new provinces also draws legitimacy from the historical role MQM played in this debate. During the early 2010s, when voices for a separate Hazara province in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and a Seraiki or Southern Punjab province in Punjab were gaining momentum, MQM seized the moment to push its own agenda. The party went so far as to introduce a constitutional amendment bill in the National Assembly calling for the creation of more provinces across Pakistan.

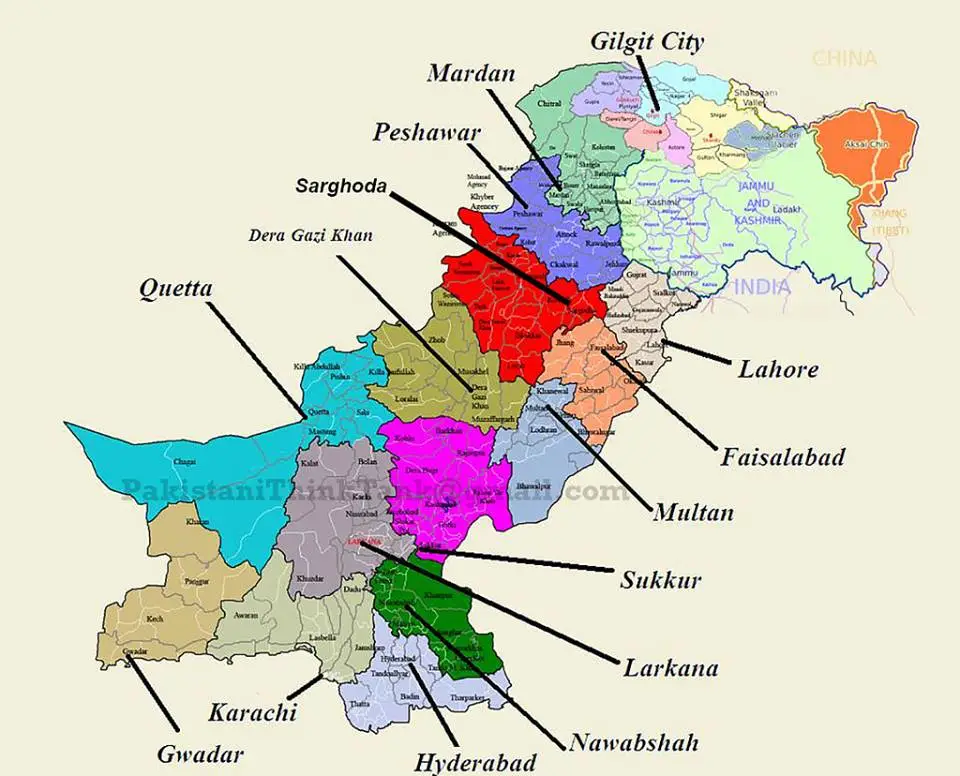

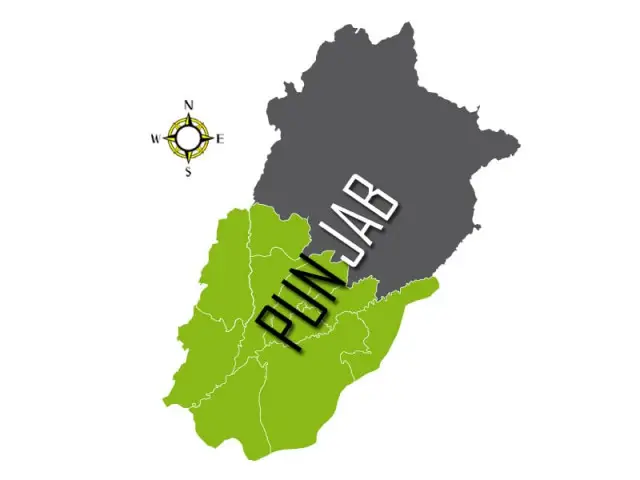

In contrast, the demands for Hazara and Southern Punjab provinces carry a degree of legitimacy, as they stem from the aspirations of local populations who believe they have been systematically marginalised. The people of Southern Punjab argue that the Punjabi elite has long exploited the resources of the Seraiki belt without addressing its chronic underdevelopment. Similarly, residents of Hazara feel they have been sidelined and treated as second-class citizens under the dominance of Pashtoon or Afghan elites.

By comparison, no such broad-based movement exists in Sindh or Balochistan, where the notion of new provinces is largely absent and often perceived as an artificial construct driven by external forces rather than genuine public demand.

On the surface, MQM attempted to portray the move as a democratic initiative to empower neglected regions. Yet, Sindhi political circles and civil society viewed it as a veiled attempt to create space for a “Mohajir province” carved out of urban Sindh.

This manoeuvre further deepened mistrust between Sindhis and the MQM. While the Hazara and Southern Punjab movements were rooted in long-standing demands of administrative autonomy and historical grievances, MQM’s intervention was seen as opportunistic and self-serving.

According to reports, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) introduced the “Constitution (20th Amendment) Bill, 2012” in the National Assembly on January 17, 2012. This bill aimed to create the Southern Punjab and Hazara provinces. It was moved by MQM’s Wasim Akhtar during a special session — specifically, on a Private Members’ Day in the National Assembly.

By tabling the amendment, MQM effectively equated its ethnic-based demand with broader regional struggles, thereby diluting their legitimacy and aggravating tensions in Sindh. For many Sindhis, this episode confirmed suspicions that calls for new provinces were less about genuine reforms and more about fragmenting existing provinces to serve narrow political ends.

Moreover, Sindhis view the timing of such debates as suspicious. Each time the call for Southern Punjab province resurfaces, MQM opportunistically revives the slogan of a Mohajir province. This pattern, they argue, is not coincidental but calculated—an establishment-backed strategy to stall Punjab’s division while simultaneously keeping Sindh’s politics in turmoil. By floating these fillers, the state diverts attention from critical issues like resource distribution under the National Finance Commission (NFC) Award, exploitation of Sindh’s natural gas, water scarcity due to upstream projects, and the systemic neglect of education and health.

A critical reading also highlights the asymmetry in how new province demands are treated across regions. While the Southern Punjab demand is rooted in administrative grievances, the Mohajir province idea is largely linguistic. To grant legitimacy to one would set a dangerous precedent for others, potentially opening Pandora’s box of ethnic divisions nationwide. Sindhis argue that the federation should instead strengthen existing provincial structures by devolving powers under the 18th Amendment, rather than multiplying units that may exacerbate conflict.

In conclusion, Sindhi opposition to new provinces is not merely emotional but anchored in a critical understanding of history, identity, and federalism. They see the establishment’s fillers and MQM’s slogans as distractions from governance failures, conspiracies to weaken Sindh’s cohesion, and attempts to shift political fault lines. For Sindh, the defense of its territorial integrity remains synonymous with the defence of its culture, history, and future within Pakistan. Any project of division, therefore, is bound to be resisted as an existential threat rather than embraced as reform.