Labour Force Survey 2024-25 is out: When we talk about Pakistan’s economy, we often think of numbers: growth rates, inflation, exports, and imports. But behind every number, there are people. Millions of men and women wake up every morning to work in fields, shops, factories, offices, homes, or on the road.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2024-25, conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, tells the real story of these people.

After a gap of two years, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) 2024-25 is providing an extensive update on the country’s labour market based on provincial-level data. The last LFS 2021-22 was released in 2023. The PBS had conducted the digital census in the entire country, so it said it was unable to release the annual LFS in 2024.

This year’s report, based on data from nearly 54,000 households across the country, paints a detailed picture of how Pakistanis work, where opportunities are growing, and where challenges remain.

What makes the LFS 2024-25 especially noteworthy is its adoption of the framework set by the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS), which is overseen by the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

The ICLS establishes comprehensive guidelines to ensure consistency and comparability in labour statistics worldwide. Before this, Pakistan had been using the 13th ICLS framework, which is now considered outdated by many countries striving to keep pace with evolving labour market complexities.

One of the biggest changes brought about by the 19th ICLS standards is the refined definition of employment, particularly the decision to exclude subsistence agriculture workers from the employed population.

The total labour force expanded significantly, growing from 71.8 million to 85.6 million between the two survey periods. This represents an annual increase of 3.5 million individuals joining the labour market. Under the 19th ICLS, the labour force size is seen slightly lower at 83.1 million, excluding certain own-use producers classified differently under the updated methodology.

Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR), however, showed a notable increase from 44.9 per cent in 2020-21 to 47.7 per cent in 2024-25 under the 13th ICLS framework.

The survey does not just give statistics; it reveals trends that help us understand the country’s direction. It tells us who is joining the workforce, who is being left behind, which sectors are expanding, how much people are earning, and what kind of work Pakistanis are increasingly shifting toward. This is the story of Pakistan’s labour market told through real-life numbers but narrated in a way that reflects everyday experience.

A Growing Workforce: More Pakistanis Step Into the World of Work

The most striking insight from this year’s survey is that more Pakistanis are entering the labour market than before. The labour force participation rate means the percentage of people aged 10 and above who are either employed or actively looking for work.

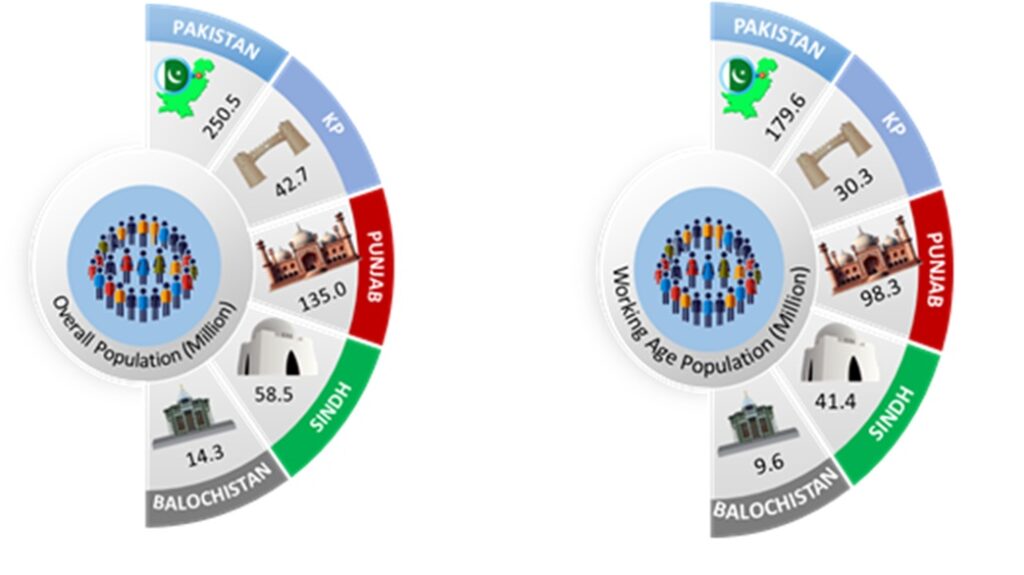

This increase may sound small, but in a country of over 250 million people, it translates into millions of new entrants. In numbers, the labour force has grown from 71.8 million to 85.6 million in just a few years. Every year, more than 3.5 million people are joining the labour market.

Men still dominate the workforce, but something remarkable is happening: more women are stepping into work, especially in rural areas. Male participation rose to 69.8 per cent, while female participation rose from 21.4 per cent to 24.4 per cent, showing a slow but promising shift. In rural areas, women’s involvement in economic activity is even more noticeable due to agriculture, livestock, and home-based work.

The country also remains overwhelmingly young. Nearly 40 per cent of Pakistan’s population is under 15, and more than 18 per cent falls between 15 and 24. This demographic wave will continue to push millions into the labour force every year, demanding more jobs, better skills, and stronger economic planning.

But more people stepping in doesn’t always mean more people finding work. The unemployment rate has inched up, from 6.3 per cent to 6.9 per cent, which means that job creation is not keeping pace with the number of people seeking employment. For women, the unemployment rate is far higher, reaching 9.7 per cent, and for young people it climbs even more. This tells us that Pakistan will have to focus on creating sustainable, quality jobs to absorb its fast-growing labour force.

Labour Force Survey 2024-25: Shifting From Farms to Services

For decades, Pakistan’s economy has relied heavily on agriculture. Even today, agriculture, forestry, and fishing still employ the largest share of workers over 35 per cent according to the older definition and around 33 per cent under the new 19th ICLS standard. But the trend is changing. Slowly but steadily, more people are leaving farm-based work and moving toward services and trade.

The survey shows that employment in agriculture decreased from 37.4 per cent to 35.1 per cent, manufacturing slightly declined, construction increased to 9.6 per cent, wholesale and retail trade grew to 15.5 per cent, and community, social, and personal services rose to 17.4 per cent.

This shift reflects Pakistan’s urbanisation, changing aspirations, and the expansion of small businesses and transport services. Still, women remain heavily concentrated in agriculture; more than 60 per cent of employed women work in the sector, while men are spread across trade, services, transport, and construction.

A major part of Pakistan’s employment scene is informal work. More than 72 per cent of non-agriculture jobs are informal, meaning they do not offer job security, written contracts, or social protection. In rural areas, informal work jumps even higher. Interestingly, women have a slightly higher presence in the formal sector than men, mostly due to their participation in education and health.

One emerging trend is the rise of digital platform work—gig work. While still a very small share (around 2.9 per cent ), it shows that Pakistanis are slowly adopting new forms of income generation such as online freelancing, delivery services, and ride-hailing platforms.

Another important aspect highlighted by the survey is the contribution of unpaid domestic and care work. Over 45 million women are engaged in household chores, livestock management, and caregiving—activities that keep families functioning but are rarely counted as economic work.

How Much Pakistan Earns: Wages, Working Hours, and the Cost of Effort

The survey also offers a deep look into how much workers earn—and whether their wages are keeping pace with living costs. The good news is that average monthly wages have increased significantly. A paid employee now earns around Rs. 39,042 per month on average, compared to Rs. 24,028 just a few years ago.

But behind this jump lies a complex reality. Inflation has eaten into much of this growth, meaning that even though people are earning more on paper, their purchasing power has not increased at the same pace. Women earn less than men, though the wage gap has narrowed slightly. Men earn around Rs. 39,302, while women earn Rs. 37,347 on average.

Working hours also tell an important story. Most Pakistanis work long hours—between 46 and 48 hours a week on average. Transport, construction, and retail workers tend to work the longest hours, while people in community services work slightly fewer.

The survey also reveals the nature of jobs people hold. Most Pakistanis are employees (43.5 per cent ), own-account workers (36.1 per cent ), contributing family workers (19.1 per cent ), or employers (1.3 per cent ).

For women, the picture looks very different. Nearly half of employed women are contributing family workers, meaning they work without pay in family enterprises.

Conclusion: A Country of Hard-working People at a Turning Point

The Labour Force Survey 2024-25 tells a story of a country that is young, energetic, and hard-working and standing at a crossroads. Pakistan’s labour force is growing faster than ever. More women are participating. The economy is slowly shifting from farms to trade and services. Wages have increased, but so have challenges. Informal work still dominates. Youth unemployment remains high. And millions of women perform unpaid labour that keeps the economy running but remains unrecognised.

This survey is more than numbers; it is a mirror reflecting the lives, struggles, and contributions of Pakistan’s workers.