Seventeen years on, the murder of Benazir Bhutto still casts a long shadow over Pakistan’s politics and its courts. The alleged killers are not behind bars serving final sentences; some were freed by the courts, and others continue to face unresolved legal proceedings. What endures is not closure, but a case that refuses to be put to rest — a reminder of how power, violence and justice collided on a winter evening in Rawalpindi.

A Turning Point in Pakistan’s Political History

There are moments in a nation’s life that divide time into a before and an after. For Pakistan, December 27, 2007, was one such moment.

That evening in Rawalpindi, Benazir Bhutto stood briefly through the sunroof of her vehicle after addressing a charged election rally at Liaquat Bagh. It was a familiar gesture, almost instinctive, as a politician reconnects with her supporters after years of exile and political isolation within her own country. Seconds later, gunfire rang out, followed by a devastating suicide blast. Bhutto collapsed inside the vehicle, critically injured. By the time she reached the hospital, she was dead.

What followed was grief on a national scale. Streets burned, cities shut down, and a sense of collective shock gripped Pakistan. The general elections were postponed, and for weeks, the country seemed suspended between mourning and uncertainty. When the polls were eventually held in February 2008, they returned Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party to power at the centre and in Sindh, transforming tragedy into political transition.

Yet while governments changed and power shifted, the central question remained unanswered: who killed Benazir Bhutto, and how?

Prolonged, Multifaced Investigations

From the outset, the case was riddled with confusion. Competing theories emerged within hours. Some officials claimed she had been shot. Others suggested she was killed by the force of the explosion. Even official versions pointed out the vehicle’s hatch injury caused her death. The crime scene at Liaquat Bagh was washed within hours, erasing forensic evidence before independent investigators could examine it. No autopsy was conducted on request from the family, a decision that would haunt every inquiry that followed.

Faced with domestic and international pressure, the government of the Pakistan People’s Party sought external help. Scotland Yard was asked to assist in determining the cause of death, while the United Nations Secretary General was later requested to examine the broader facts and circumstances surrounding the assassination.

The British investigators’ mandate was limited, and their findings reflected those constraints. In a report made public in early 2008, Scotland Yard concluded that Bhutto did not die from gunshot wounds but from a fatal head injury caused by the blast’s impact, likely when her head struck part of the vehicle’s escape hatch. The report rejected the interior ministry’s initial claim that two attackers were involved, concluding instead that a single assailant fired shots and then detonated the bomb.

But the report also read like a catalogue of what could not be done. There was no autopsy. Medical imaging was incomplete. The crime scene had been contaminated beyond repair. The investigators could say how Bhutto likely died, but not why her security failed so catastrophically, or how an attacker managed to reach her at arm’s length in one of the most heavily guarded political events in the country.

Privately, even government officials expressed dissatisfaction. The findings clarified little beyond reinforcing what many already suspected: the investigation had been compromised almost from the start.

If the Scotland Yard report disappointed those hoping for definitive answers, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry, established in 2009, offered a different kind of reckoning. Its report, released in April 2010, was blunt in its assessment. Benazir Bhutto’s assassination, it concluded, was preventable. The security provided to her was “fatally insufficient,” and the subsequent investigation was marred by obstruction, poor coordination and inexplicable decisions.

Yet the UN commission, too, stopped short of naming those responsible. It was not a criminal court, and it made clear that fixing individual guilt lay beyond its mandate. Instead, it painted a disturbing picture of institutional failure, a state unable or unwilling to protect one of its most prominent political leaders, and then unable to investigate her killing with credibility.

Benazir Bhutto Assassination: Search for Accountability

That burden ultimately fell on Pakistan’s own courts, where the search for accountability took a long and uneven course. Over the years, several men alleged to be linked to militant groups, including the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, were arrested and charged. At trial stages, anti-terrorism courts handed down severe sentences, including capital punishment, reinforcing the official narrative that Taliban operatives were behind the assassination.

But the courtroom proved a harsher arena for the prosecution than public opinion. Evidence collected from a compromised crime scene failed to stand up to scrutiny. Witnesses proved unreliable. Key suspects were either dead or beyond the reach of the courts. In 2017, nearly ten years after the assassination, an anti-terrorism court acquitted five accused militants due to a lack of evidence. Two senior police officers were convicted, not for murder, but for negligence and for failing to properly investigate the crime. Former president and Military chief General (Retd.) Pervez Musharraf, charged in absentia, was declared a fugitive.

The verdict left behind an uncomfortable paradox. At different points, alleged Taliban operatives had been sentenced to death for Benazir Bhutto’s killing, yet no conviction ultimately survived the legal process. International investigations exposed failures but fixed no responsibility. Domestic trials delivered punishment at one stage and acquittal at another. The truth, it seemed, was dispersed across reports, judgments and unresolved suspicions.

For many Pakistanis, the case has come to symbolise something larger than a single crime. It reflects the fragility of institutions, the costs of political violence, and the ease with which justice can be delayed until it is diluted. Benazir Bhutto’s assassination changed the course of the country’s politics, but the failure to conclusively resolve her killing has left a lingering wound in the national conscience.

History will remember her as a twice-elected prime minister, a symbol of democratic resistance and a deeply polarising figure. But it will also remember that in her death, as in much of her life, the promise of accountability remained unfulfilled.

What Happened to Police Officers Accused of Lapses

The Benazir Bhutto murder case continues to wind its way through the courts and remains sub judice, with no final judicial closure in sight. Multiple appeals, including challenges to the acquittal of the accused militants and petitions filed by the convicted police officers, have been taken up from time to time by the Lahore High Court and other benches, with proceedings scheduled to resume in September 2024 after prolonged adjournments.

On August 31, 2017, nearly 11 years after the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, an Anti-Terrorism Court (ATC) in Rawalpindi delivered its long-awaited verdict in the case.

The court convicted former Rawalpindi City Police Officer Saud Aziz and Superintendent of Police Khurram Shahzad, sentencing each to 17 years’ imprisonment and imposing a fine of Rs 10 million for negligence and mishandling of security and investigation. Both officers were taken into custody immediately after the judgment.

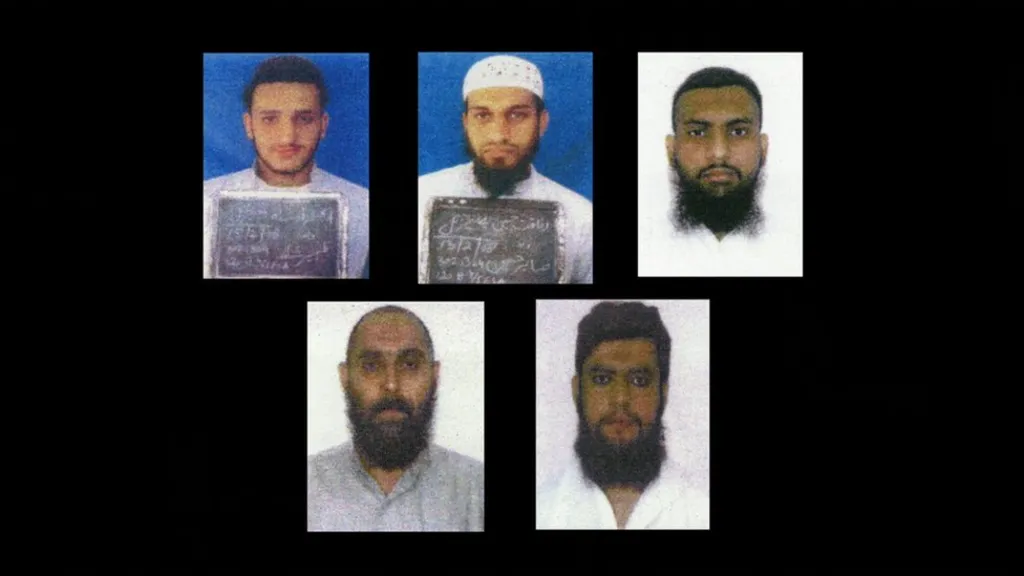

In the same ruling, the court acquitted five other accused, Aitzaz Shah, Sher Zaman, Rafaqat, Hasnain and Abdul Rasheed, while issuing permanent arrest warrants for former President Gen (retd) Pervez Musharraf, who was abroad at the time, and ordering the confiscation of his property.

The verdict was followed by a flurry of legal challenges: the two convicted officers filed separate appeals seeking acquittal; Asif Ali Zardari filed three appeals demanding Musharraf’s sentencing in absentia, his return to Pakistan, and the reversal of the acquittals; and the Federal Investigation Agency lodged five appeals seeking Musharraf’s conviction, the sentencing of the acquitted accused, and enhanced punishment for the two police officers.

Subsequently, three of the acquitted men, Aitzaz Shah, Sher Zaman and Hasnain were released on bail. Rafaqat disappeared after his release, while Abdul Rasheed remains incarcerated in Adiala Jail, where he has spent approximately 17 and a half years in custody.

Conclusion

Nearly seventeen years after Benazir Bhutto was assassinated, the case continues to move slowly through the courts, weighed down by appeals, adjournments and unresolved questions. With the matter still sub judice and the Lahore High Court periodically revisiting challenges to both acquittals and convictions, the 2017 verdict remains provisional rather than final. Until a conclusive appellate judgment is delivered, the legal record of Pakistan’s most consequential political murder will remain unsettled, reflecting not only the complexity of the case, but also the enduring difficulty of delivering closure in crimes that sit at the crossroads of power, politics and violence.