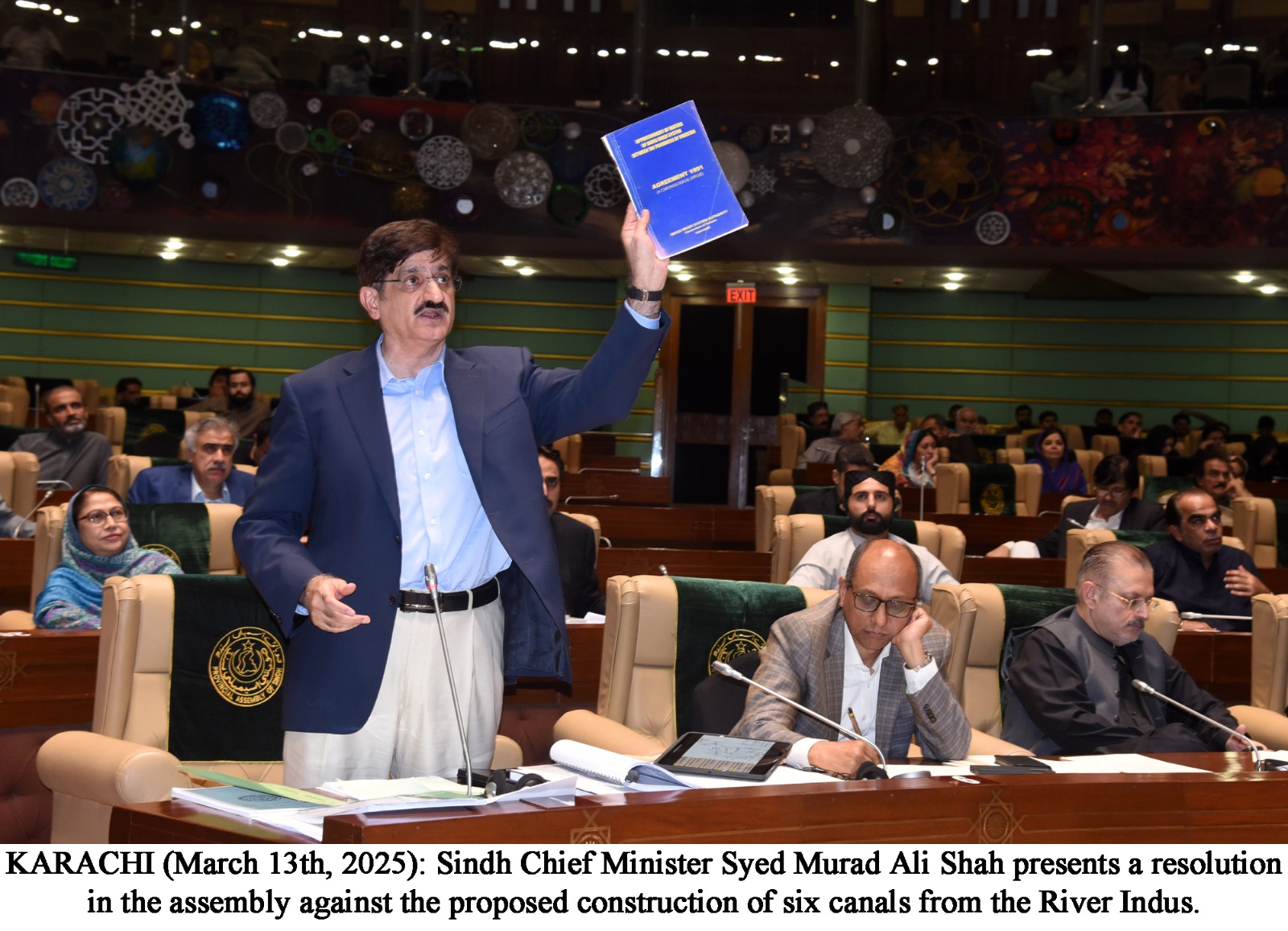

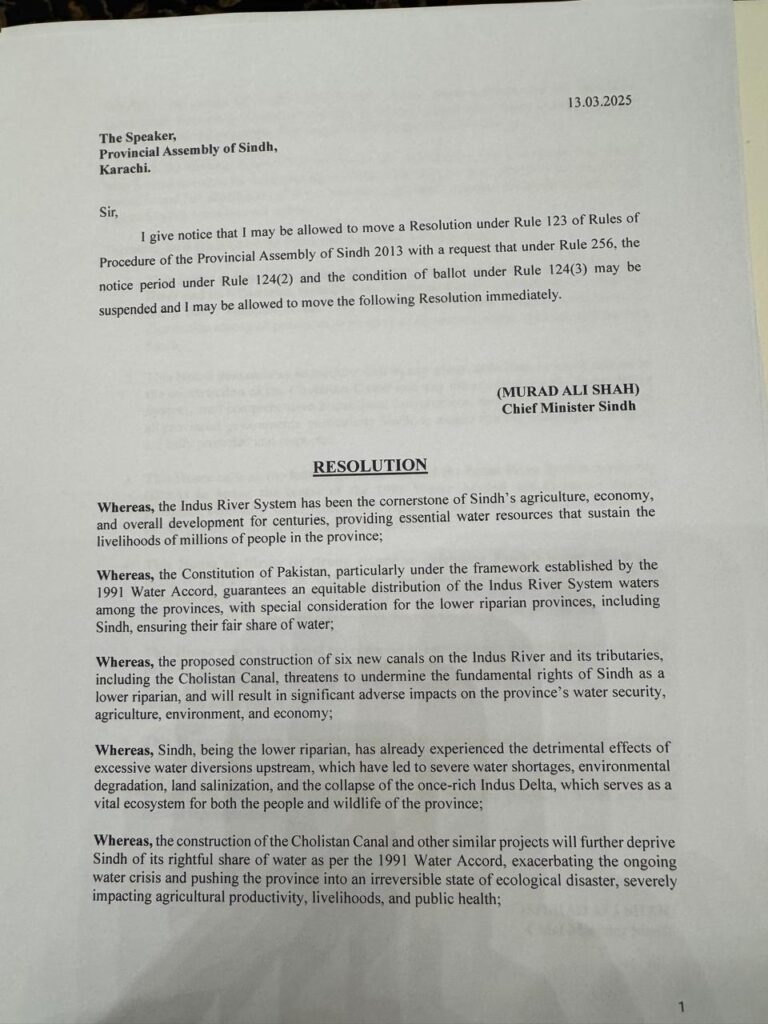

Finally, on Thursday, the Sindh Assembly approved a motion vehemently denouncing the building of new 6 canals, including the Cholistan Canal and Greater Thul Canal, on the Indus River system. Supported by all members, the Sindh Chief Minister and Leader of the House, Syed Murad Ali Shah, offered a resolution calling for an immediate stop to any work on these projects until thorough agreements are reached with all province governments, especially Sindh, to protect its water rights.

Emphasising that the project is against the 1991 Water Accord and jeopardises inter-provincial cooperation, the Chief Minister Syed Murad Ali Shah and the assembly’s position show great worries about water distribution and the possible effects on Sindh’s agricultural industry, which has always depended on the Indus River.

Part of a larger and more significant “Green Pakistan” project headed by the military leadership via the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SICF), Sindh has been opposing the building of six canals, most of them located in Punjab. Two small canals will be located in Sindh and Balochistan. Agriculture and livestock is on top of the many other targeted sectors SICF identifies.

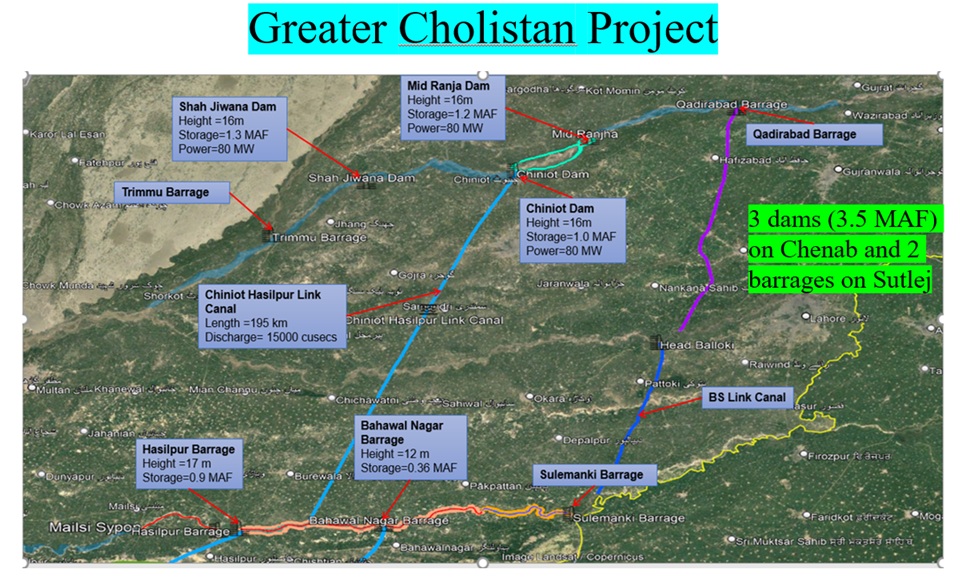

Growing farmland requires irrigation water. Under the scheme, corporate farming in the agricultural sector has acquired hundreds of thousands of acres of desolate land in Punjab’s Cholistan desert.

Said the Chierf Minister, “We are being told that water will be taken from Punjab’s most fertile lands and diverted to Cholistan and that we should not object; Punjab would allow its most productive regions, like Chaj Doab and Rachna Doab, to dry up just to irrigate a desert.”

Earlier, in his presidential speech to the joint sitting of the Parliament at the beginning of the new parliamentary year, President Asif Ali Zardari, who also leads the Pakistan People Party (PPP) that rules in Sindh, had also asked the federal government to avoid construction of the controversial six canals. Critics of President Zardari, however, object to his acceptance of the building of these canals.

Every major political party in Sindh, nationalists, civil society, lawyers, students, women, and workers have been organising demonstrations throughout Sindh calling for the federal government to halt the building of these canals.

Many political parties and civil society groups have scheduled many rallies and events on March 14, International Rivers Day to denounce Punjab’s water theft of Sindh.

Even before Pakistan was founded, the water conflict between Sindh and Punjab is decades old. Living in Indus, Sindh at the tail end, Sindh has been lamenting a water flow scarcity. Once rich because of river water flow in the sea, the Indus Delta has become barren most of the year as dams and barrages building at the upper stream have halted water flow most of the time. It is even not occurring since the 1991 Water Apportionment Accord, which had permitted 10 million acre feet of water to flow downstream Kotri barrage.

Sindh accuses Punjab of water theft from its portion. Saying there is not enough water in the Indus River system, Sindh has resisted the construction of Kalabagh Dam and drawing canals from them in the past. The same reasoning holds that six canals will not be able to get water from the river as it is scarce. Sindh believes that its portion will be pilfers in order to experience those six canals. It is a matter of the fact that under the Indus Basin Treaty with India, India has already given hold of three major rivers that flow into Indus.

The water of those three Eastern Rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) was given to India by the military rulers under the treaty. Pakistan had acquired control of three Western rivers: the Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab.

Saying that these new 6 canals would not damage Sindh’s share since they will take water from Punjab’s share as stipulated under the 1991 Water Accord, the federal government as well as Punjab government officials are fervent supporters of the building of six canals. Unlike in the past, Sindhis mistrust the Punjab, as it has been pilfering Sindh’s share by channelling water via seasonal canals like the Chashma Jhelum Link Canal. Instead of awaiting the flood season, this canal is let run all year. Moreover, Sindh’s suspicion of upper Raparrian Punjab is reasonable because her share in water has not been given anytime since the 1991 Water Accord.

Every society depends on water for agriculture, ecology, and livelihoods. However, disagreements and mistrust over the distribution and use of water can lead to national conflict, as is the case in Pakistan between Sindh and Punjab.

The conflict over water sharing in the Indus system is not new in Pakistan, as it dates back to the pre-partition era, after the construction of the Sukkur barrage in the 1930s. Concerns regarding water rights, environmental sustainability, and governance have grown in Sindh as a result of Punjab’s construction of six new canals.

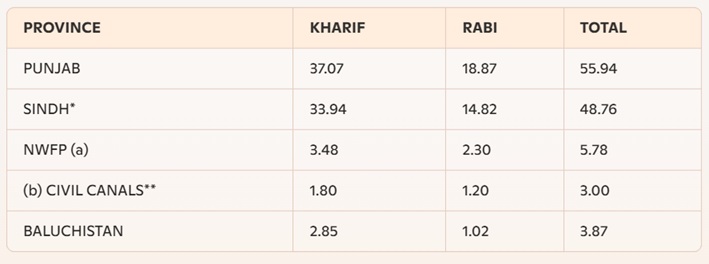

Here is what the 1991 Water Accord says:

** Engaged Civil Canals above the rim stations.

Details of New 6 canals?

According to senior columnist and civil society activist Mr. Naseer Memon, these controversial canals include the Chubara Canal as the second phase of the Greater Thal Canal, the Kachhi Canal, the Rainee Canal, the Thar Canal, the Chashma Right Bank Canal, and the Cholistan Flood Feeder Canal. The total command area of these canals is 3.58 million acres.

Mr. Memon claims that Sindh is not sure about the new irrigation projects, mostly because of inadequate water availability in the Indus basin. For 1976 to 1998, the average annual flow below Kotri Barrage was 40.69 MAF. From 1999 to 2022, the flow dropped sharply to 14 MAF. The Indus delta is about to experience an ecological catastrophe. Changing the climate is worsening the water situation. Building new canals in these circumstances would fan fresh tension between Sindh and Punjab.

Conflict aggravates

The federal government’s Central Development Working Party (CDWP) gave approval of the construction of six canals. The government of Punjab has authorised the building of six canals on the province’s rivers. By supporting corporate farming in the Cholistan desert, these canals hope to modernise agriculture, improve food security, and make use of underdeveloped terrain.

Citing serious worries about water scarcity and fair distribution under Pakistan’s water management system, Sindh has strongly objected to the canal’s construction. Let’s examine their main points in more detail:

Conflict over Approval with Council of Common Interests (CCI)

The Council of Common Interests’ (CCI) inadequate approval of the six canals’ construction is one of Sindh’s main grievances. As a constitutional agency, the CCI is in charge of resolving conflicts between provinces and guaranteeing fair resource distribution.

According to Sindh, it was disregarded during the decision-making process, which they say is against the prescribed procedure for projects involving water. Sindh is now more afraid of being left out of talks that have a significant influence on its water resources as a result of this lack of transparency. The CCI needs to take the initiative to mediate complaints and settle conflicts. In politically delicate projects, avoiding the CCI only serves to increase provincial mistrust.

Making Water Equity a Priority

All provinces must receive their fair share of water through the strict observance of the Water Apportionment Accord of 1991. Rebuilding stakeholder trust requires transparent procedures.

Evaluations of Environmental Impacts

Large-scale projects should undergo thorough Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) prior to approval. To guarantee sustainability, results should be made public and reviewed by impartial specialists.