The Sindh Tenancy Act, 1950, landmark legislation intended to regularise the relationship between landlords (Zamindars) and peasants (Haris) and safeguard the rights of the latter, is now widely considered redundant and largely unimplemented in its true spirit across the Sindh province.

In a significant move signalling a serious judicial commitment to protecting the rights of agricultural tenants, the Supreme Court of Pakistan’s Karachi Circuit Bench has intervened decisively in a long-standing land dispute, issuing a landmark order that forces Sindh’s top revenue bodies to undertake a comprehensive, Taluka-by-Taluka audit of all registered permanent tenant farmers, or Haris.

Under the Sindh Tenancy Act 1950, the Taluka revenue officers are bound to register all peasants and keep a record of them on an annual basis. However, such a practice has not been done anywhere in the province for many years.

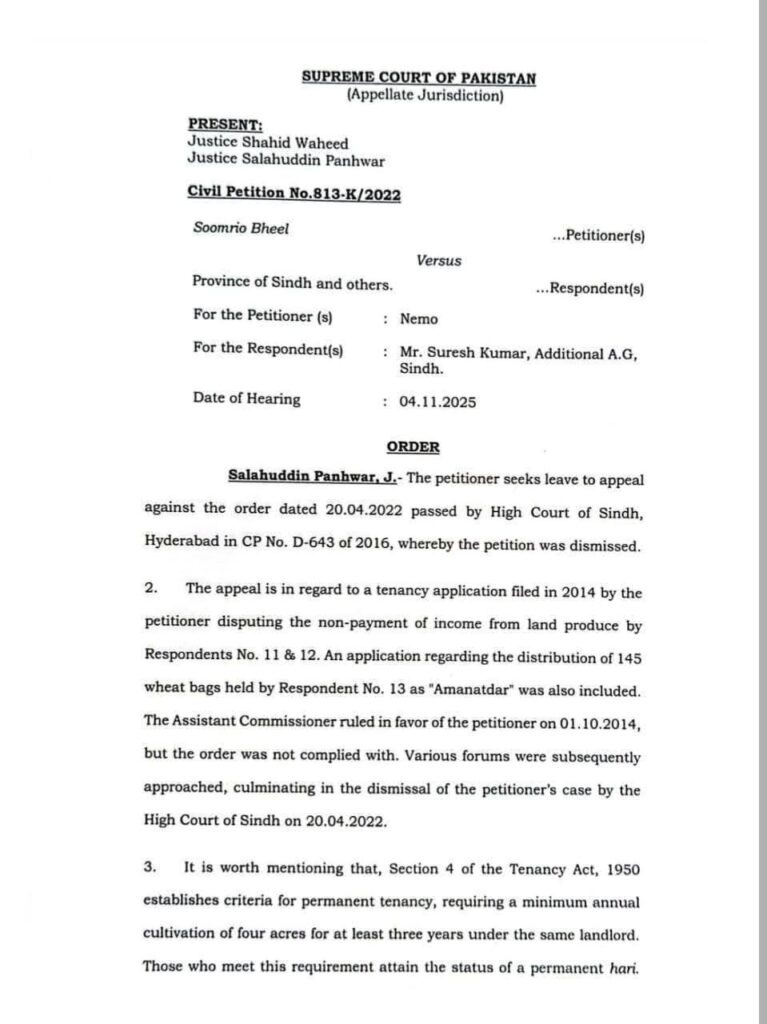

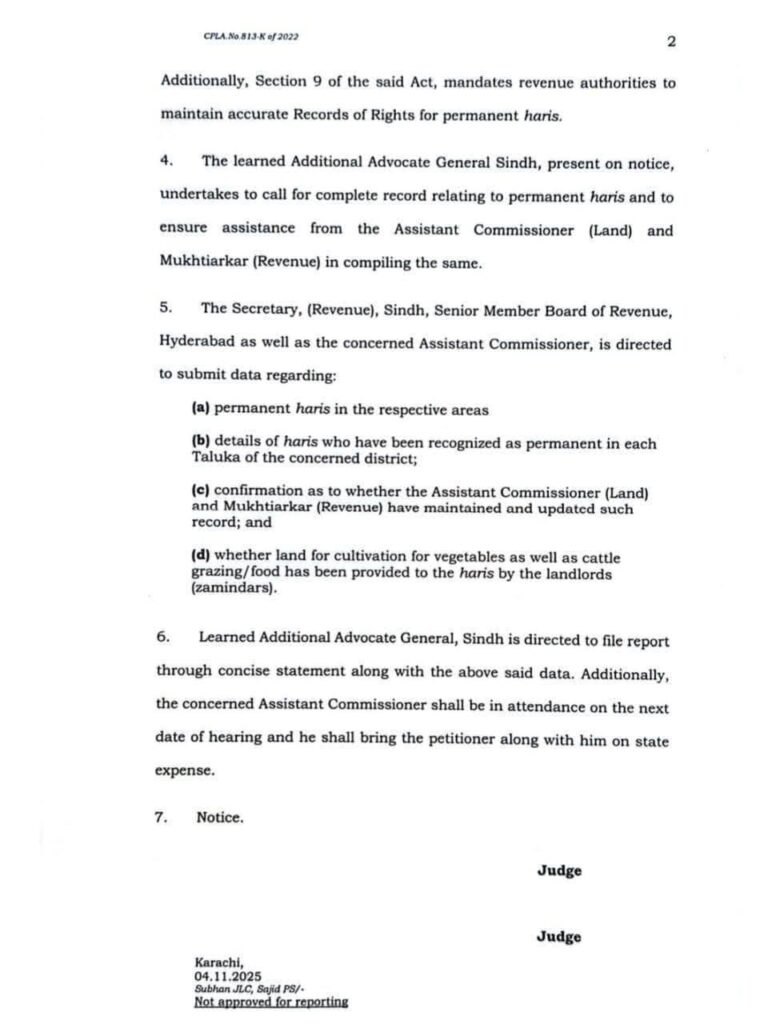

The SC directive, delivered by a bench comprising Justice Shahid Waheed and Justice Salahuddin Panhwar, goes far beyond the scope of the original petition, highlighting systemic lapses in the maintenance of legally mandated land records and the enforcement of the Sindh Tenancy Act of 1950.

It is worth noting that the same judge, Justice Salahuddin Panhwar of the Sindh High Court’s Hyderabad Circuit Bench, had earlier delivered another landmark judgement in 2019 in the late Ghulam Ali Leghari of Sanghar case. Leghari was also a victim of a landlord in Sanghar district, who expelled him from the land and burnt his home and refused to pay his proper share of many years’ labor. He died of Hepatitis C, and later his son fought his case in Sindh High Court Hyderabad Bench, where the same judge gave a landmark verdict.

That 2019 ruling by the SHC bench was a turning point in redefining the relationship between landlords, peasants, and the revenue administration. In his detailed verdict on a petition filed by peasant Leghari, Mr. Justice Panhwar transferred the judicial authority in land disputes from the executive to the judiciary, thereby ensuring greater transparency and fairness. The judgement also struck down a controversial amendment that many critics believed had effectively legitimised bonded labour (Beghar), marking a major step forward in protecting peasants’ rights in Sindh.

Despite the landmark nature of the 2019 judgement, the provincial government later filed an appeal against the pro-peasant verdict in the Supreme Court, a move that drew severe criticism from the Hari (peasant) organisations and other human rights organisations. The case of Soomrio Bheel, currently before the Supreme Court, suggests that the struggle for transparent land records and the enforcement of the 1950 Act remains highly relevant years after the Leghari verdict.

The Sindh government’s appeal against the Leghari case is still pending before the apex court. However, this landmark judgement must be implemented in its true letter and spirit. Civil society groups and human rights organisations have a crucial role to play in ensuring its enforcement.

It is an undeniable fact that the provincial government, overwhelmingly dominated by Sindh’s landlords and feudal elites, has shown little seriousness in addressing the concerns of peasants. Time and again, it has avoided taking concrete steps that could genuinely protect and empower the Haris (peasants) who form the backbone of Sindh’s rural economy.

Sindh Tenancy Act—Latest SC Order

The case, Civil Petition No. 813-K/2022, was brought by petitioner Soomrio Bheel from the village Karamullah Dahri near Shahdadpur, district Sanghar, who is challenging the dismissal of his earlier petition by the High Court of Sindh on April 20, 2022. Bheel’s original application, filed over a decade ago in 2014, revolved around a dispute with multiple respondents concerning the non-payment of income derived from land produce.

A lawyer in Sanghar Housh Mohammad Mangi who had provided legal support to Mr. Bheel at the assistant commissioner level, told this scribe that the steadfast peasant raised his dispute with Zamindar Qadir Bukhsh Sanjrani as the latter violated the tenancy law’s rule and refused to give him his due share.

Adding complexity to the financial claim by Bheel was a specific application demanding the distribution of 145 bags of harvested wheat, which were held by Zamindar in the capacity of an Amanatdar (a trustee or custodian). While the Assistant Commissioner (AC) had initially found in favour of the petitioner on October 1, 2014, that order was reportedly never complied with. The petitioner was subsequently forced to pursue justice across various judicial and administrative forums, only to face a final setback with the High Court’s dismissal.

The Supreme Court bench, in its order authored by Justice Panhwar, grounded its intervention firmly in the legal structure governing agricultural land relations.

The order meticulously referred to Section 4 of the Tenancy Act, 1950, which provides the statutory definition for achieving the coveted status of a permanent Hari. To qualify, an individual must have cultivated a minimum of four acres of land annually for at least three consecutive years under the same landlord.

The court further emphasised Section 9 of the same act, which is a categorical legislative mandate requiring revenue authorities (earlier a Mukhtiarkar and now an Assistant Commissioner) to “maintain accurate Records of Rights for permanent Haris.” The very nature of the dispute, which had lingered for over eight years, strongly suggested that this crucial legal duty had been neglected.

Recognising the broader implications for the farming community, the Supreme Court pivoted from simply addressing Bheel’s individual plight to initiating a provincial-level audit. The order immediately tasked the Additional Advocate General (AAG) Sindh, who was present on notice, with undertaking the responsibility to secure the “complete record relating to permanent Haris” and ensuring full assistance from the local land revenue officials, the Assistant Commissioner and Mukhtiarkar (Revenue), in this vital compilation process.

Lack of Registration of Peasants

The most extraordinary part of the directive, however, was the data mandate issued to the most senior revenue functionaries. The Secretary (Revenue), Sindh, the Senior Member of the Board of Revenue, Hyderabad, and the concerned Assistant Commissioner were jointly and severally directed to submit specific, verified data points, including:

- (a) The comprehensive list of all permanent Haris in the respective areas under their jurisdiction.

- (b) Precise details of Haris are officially recognised and recorded as permanent in each Taluka of the concerned district.

- (c) A formal confirmation stating whether the Assistant Commissioner (Land) and Mukhtiarkar (Revenue) have faithfully maintained and updated the Records of Rights as required by law.

- (d) Critical information regarding whether land has been allocated by the landlords (zamindars) to the Haris for ancillary activities like cultivating vegetables and for essential cattle grazing or food.

This detailed requirement transforms the judicial process into an investigative audit of land management and tenant welfare. The AAG Sindh is now required to file a report incorporating all this comprehensive data and a concise statement to the court.

Furthermore, to ensure the attendance and cooperation of the original petitioner, the Supreme Court directed the concerned Assistant Commissioner to be present at the next hearing and to ensure that Soomrio Bheel is brought along with him at state expense.

This last instruction serves as a powerful symbol of the court’s intent to uphold the dignity and rights of the vulnerable petitioner. The outcome of this case is expected to have far-reaching implications for land governance and the rights of tenant farmers across Sindh.